Cambodia election: ‘This was more of a coronation than an election’

Cambodia election: ‘This was more of a coronation than an election’

Motorbikes carrying cheering, flag-waving supporters of Cambodia’s ruling party revved their engines despite the pouring rain ahead of their triumphant final rally in downtown Phnom Penh.

As far as the eye could see, people lined the road, party stickers on their cheeks, and their sky-blue hats and shirts getting steadily wetter.

Atop a truck, Hun Manet, the 45-year-old eldest son of Prime Minister Hun Sen, addressed the crowd, declaring that only the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) was capable of leading the country.

As a matter of fact, his father had ensured that the CPP was the only party that could win.

Known for his pugnacious style, Hun Sen has ruled Cambodia for 38 years: first under a communist regime installed by Vietnam, then under a multi-party system installed by the UN, and more recently as an increasingly intolerant autocrat.

In May, the Candlelight Party, the only party capable of challenging his rule, was disqualified from the election on a technicality. There were 17 other parties that were allowed to participate, but they were too small or unknown to pose a threat.

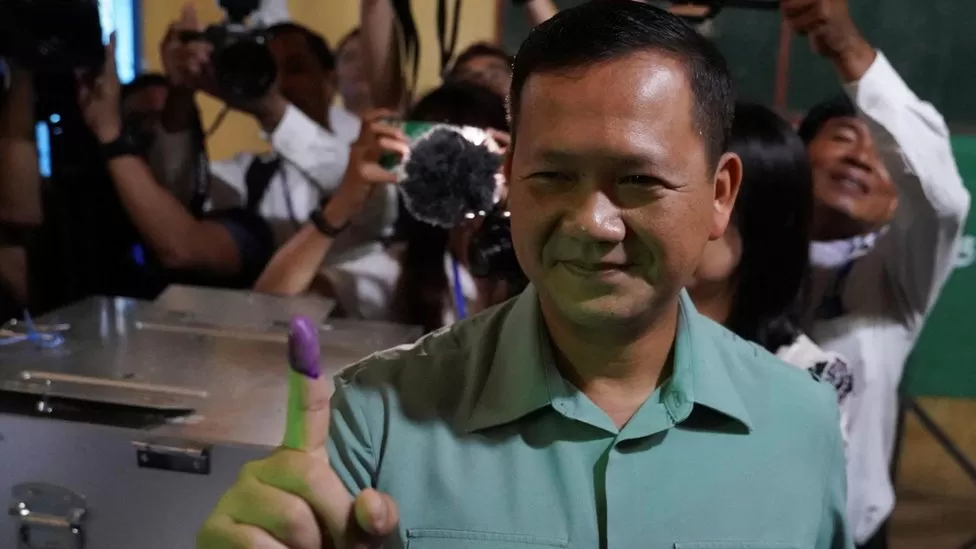

Several hours after the polls closed, the CPP claimed a landslide victory with a turnout of more than 80%. Several polling stations had spoiled ballot papers: that was probably the only safe way for voters to show their opposition support.

This election felt more like a coronation than an election, since Hun Manet was expected to succeed his father within weeks of the vote.

Mu Sochua, an exiled former minister and member of the CNRP, another opposition party banned by the Cambodian government in 2017, says the elections were not a sham.

In order to continue the dynasty of the Hun family, Hun Sen should conduct a ‘selection’ for his son to become Cambodia’s next prime minister.

However, there were signs of nervousness in the CPP before the vote. A new law was passed hurriedly criminalizing any encouragement to spoil ballots or boycott an election. A number of Candlelight members were arrested.

Ou Virak, founder of the Cambodian think tank Future Forum, asks, “Why did the CPP campaign so hard against no one in this election?”

“They knew they would win the election – that was an easy outcome for them. But gaining legitimacy is a much more difficult process.”

As long as they weaken the opposition, they must also satisfy the people, so that previous setbacks and disruptions, such as street protests, do not repeat.

One of Asia’s great survivors, Hun Sen is a wily, street-smart politician who has repeatedly outmanoeuvred his opponents. Against the US and Europe, which are trying to reclaim lost influence in the region, he has skillfully played off China, by far the largest foreign investor today.

However, he has come close to losing elections in the past. The Cambodian economy could suffer a sudden downturn which could sour public opinion against him, as well as rival factions within his own ruling party. He is trying to cement his legacy as he prepares for a once-in-a-generation leadership transition.

Win-Win memorial, a 33m-high concrete-and-marble monolith north of the capital, was constructed recently.

In echo with Cambodia’s greatest historic monument, Angkor Wat, its massive base is carved with stone reliefs.

They depict Hun Sen’s flight from Khmer Rouge-ruled Cambodia to Vietnam in 1977, his triumphant return with the invading Vietnamese army in 1979, and his eventual deal in 1998 with the last of the Khmer Rouge leaders to end the long civil war – his win-win for Cambodians.

The main claim to legitimacy of Hun Sen has long been the delivery of peace and prosperity. Despite a very low starting point, Cambodia has had one of the fastest-growing economies in the world since 1998.

It is a model of growth that has concentrated wealth in the hands of a few families – such a low-income country has so many ultra-luxury cars on its roads. Many ordinary people feel that under Mr Sen they are not winning because it has encouraged rapacious exploitation of Cambodia’s natural resources.

Prak Sopheap lives with her family at the back of an engine repair shop, wedged between the main road and one of the many shallow lakes outside Phnom Penh. They have been fishing and cultivating vegetables on the lake for 25 years.

A property developer has filled much of the lake with rubble today, and Ms Sopheap’s family has been asked to leave.

She showed me a document from the local council confirming how long she had lived there, as well as a summons to court for illegally occupying state land. In addition to feeling powerless and angry, she is not the only one feeling this way.