China’s new move in microchip war means for world

As the chip war with the US heats up, China is set to restrict exports of two materials key to the semiconductor industry.

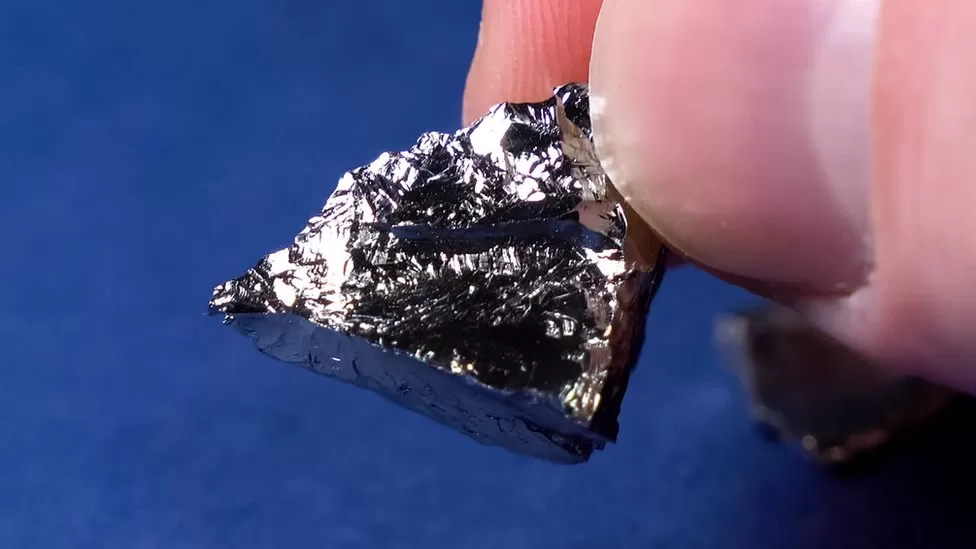

Exports of gallium and germanium from the world’s second largest economy will require special licences.

Chips are made from the materials, and they have military applications as well.

As a result of Washington’s efforts to restrict Beijing’s access to advanced microprocessors, Beijing has been subjected to these curbs.

Gallium and germanium are by far the most important elements in the global supply chain. Globally, it produces 80% of the gallium and 60% of the germanium, according to the Critical Raw Materials Alliance (CRMA).

As minor metals, these materials are not typically found in nature on their own, and are often by-products of other processes.

Aside from the US, Taiwan, Japan, and the Netherlands – where ASML, a key chip maker, is based – also impose export restrictions on chip technology from China.

As Colin Hamilton from BMO Capital Markets told the BBC, the timing of China’s announcement is not coincidental given the Netherlands’ restrictions on chip exports.

“Quite simply, if you don’t give us chips, we won’t give you the materials to make those chips,” he said.

Concerns have been raised over the rise of so-called “resource nationalism” – when governments hoard critical materials in order to exert influence over other countries.

The University of Birmingham’s critical materials research fellow Dr Gavin Harper says governments are moving away from the narrative of globalization.

Western industry might be facing an existential threat if you look at the situation more broadly. The idea that international markets will simply supply materials is gone.

A compound of gallium and arsenic, gallium arsenide is used in high-frequency computer chips as well as light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and solar panels.

The CRMA reports that only a few companies around the world produce gallium arsenide that is pure enough to use in electronics.

Microprocessors and solar cells are also made from germanium. Also, it is used in vision goggles that are “key to the military,” according to Hamilton.

“There should be enough regional supply from base metal smelters to provide alternatives. Top quality semiconductors are a harder problem, since China is really dominant. There might be some recycling,” said Hamilton.

As of last month, the US had a stockpile of germanium but none of gallium, according to a Pentagon spokesperson.

According to the spokesperson, “[the Defense Department] is taking proactive steps to increase domestic mining and processing of critical materials for microelectronics and space.”

Long-term, the Chinese export restrictions are expected to have a limited impact.

Despite China’s dominance in gallium and germanium exports, there are substitutes for the materials in computer chips, according to political risk consultancy Eurasia Group.

As well as mining and processing facilities in China, there are also facilities outside the country.

Similar restrictions were imposed by China over a decade ago on rare earth minerals exports.

China’s dominance of the rare earths supply chain fell from 98% to 63% in less than a decade, according to Eurasia.

According to Anna Ashton, Eurasia’s director for China corporate affairs and US-China, “We can expect to see the development and exploitation of alternative sources of gallium and germanium, as well as greater efforts to recycle these commodities and identify more readily available alternatives.”

Those restrictions aren’t just going to result from China’s recent announcement,” she added. China’s documented willingness to restrict imports and exports in service of political and strategic ends has contributed to rising demand, intensifying geostrategic competition, and distrust.”

No matter where chips are made, Washington has announced it will require licenses from companies exporting them to China using US software or tools.